Apple, Antitrust, and Virtue

Last week the Justice Department filed suit against Apple for antitrust violations associated with its iPhone. Is there virtue in it? How does this compare to antitrust cases in times past?

Justice Briefs is a weekly newsletter devoted to federal criminal prosecution. The federal government’s evolution over the last 230 years has given federal prosecutors significant discretion. Few realize it exists and even fewer know how it is used. Justice Briefs aims to make federal prosecutions and prosecutors more accessible to the general public. Please help me in this endeavor by subscribing and sharing with others.

Justice in Brief

*In the Western District of Kentucky, a former Kentucky probation and parole officer was sentenced for violating the civil rights of three of his female probationers by sexually assaulting them.

*In the District of Maryland the son of a civillian Navy employee stationed in Bahrain was sentenced to more than 16 years for murdering his mother. The son was living as her dependent. The United States had jurisdiction under the Military Extraterritorial Jurisdiction Act.

*In the District of Rhode Island a man who defrauded investors for over 10 years received an eight-year sentence. The man promoted certain investments, promising a quick return, when, in fact, he used the money for personal use.

Apple and Antitrust - Then and Now

On March 21, the Justice Department announced that it filed a complaint in the District of New Jersey alleging that Apple committed antitrust violations. Apple, according to the complaint, violated Section 2 of the Sherman Antitrust Act. That section prohibits anyone from monopolizing or anttempting to monopolize any part of the trade between states or foreign nations. The complaint alleges that Apple used its market power and control over the iOS platform to restrain trade in multiple ways. The case raises questions about the new technological world we inhabit and whether an industrial age law that was virtuous at the time holds the same virtue today.

The Justice Department’s complaint lists numerous methods Apple uses to suppress competition. These methods continue to evolve with technology. According to the Justice Department, Apple:

“distrupted the growth” of apps that made switching between platforms (such as Microsoft to Apple) easier

“blocked the development” of apps and services that streamed high-quality video without the use of high-priced software

made the “quality of cross-platform messaging worse, less innovative, and less secure for users” so that users had to use the iPhone

“limited the functionality of third-party smartwatches” so that users had to purchase iPhones to have full capability

“prevented third-party apps from offering tap-to-pay functionality” thus impairing the development of third-party electronic wallets

The Justice Department contends that Apple did this to maintain and expand control over emerging technology and innovative electronic devices.

Importantly, the Justice Department did NOT file criminal charges against Apple. Had it filed criminal charges, Apple could receive a $100 million fine. Although this sounds like a lot, it pales when compared to Apple’s annual $383 billion revenue and $97 billion in net proceeds. Apple’s executives could be fined $1 million and receive 10 years in prison. Instead, the Justice Department sought equitable relief, an outcome where Apple must stop its practices.

Near the end of its press release, the Department noted that it has been enforcing the Sherman Act for over 100 years. Over that time, how the Department has enforced the Sherman Act has changed.

The Department’s antitrust enforcement began slowly. The Sherman Act was passed in 1890 but enforcement lagged behind for two inter-related reasons. First, the law itself was vague. Critics argued that it could be applied to anyone for any conduct. Even those who supported the law had questions about its application. This led the second reason. The first efforts to enforce the Act had to be sucessful. This required careful preparation and highly skilled attorneys. Unfortunately, these were in short supply during the early 1900s. Most United States Attorneys and their assistants did not have the ability or inclination to pursue such complicated and uncertain cases.

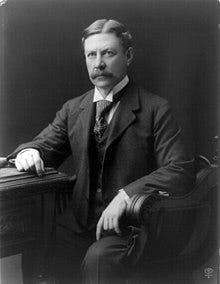

This changed in 1904. Theodore Roosevely embarked on his first elected term as President after assuming the office after President McKinley’s assassination. When Attorney General Philander Knox accepted an appointment to the United States Senate, Roosevelt appointed William Moody. He implemented Roosevelt’s main instruction: prosecute the “bad” trusts. Moody realized he could not do this on his own. He needed the help of United States Attorneys.

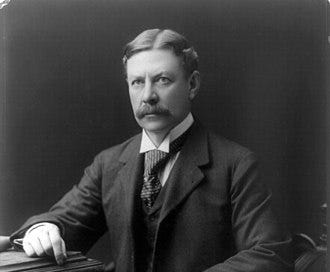

In 1906, the office of the United States Attorney for the Southern District of New York opened. Roosevelt looked to his Secretary of State, Elihu Root, who had previously served as United States Attorney for the Southern District of New York, to recommend a candidate. Root connected Roosevelt with Henry Stimson, who had been Root’s law partner. Stimson was part of an emerging breed of lawyer: the corporate lawyer. His practice entailed representing corporations in a variety of legal matters. This experience honed his legal skills and familiarized him with how corporations functioned. After clearing political obstacles, Roosevelt appointed Stimson and Moody delivered instructions: enforce antitrust laws.

Stimson quickly identified his first target: The American Sugar Refining Company. Among other activities, American Sugar collected rebates from railroads in violation of the 1903 Elkins Act. American Sugar and other companies negotiated lower shipping rates from the railroads. The railroads were dependent on large companies so the companies could dictate prices below posted tariff rates. The railroads “rebated” the difference between the posted price and the negotiated price to the company.

Over the next ten months Stimson and Moody worked together building a case. One concern was whether corporations could he held liable for acts taken by their agents. To settle that question, Stimson brought a test case. Only this was not a civil case. It was a criminal prosecution. They brought a single count to simplify the case and settle the legal questions. After a trial, American Sugar was found guilty. This led to many more criminal prosecutions and the evolution of antitrust law.

Two different cases. Two different times. Two different approaches. Is either virtuous? Returning to the Founder’s virtues sheds light on the question.

Both cases were sincere. Yesterday and today, the administration acted upon what they believed were sincere motives. They believed they were improving society as a whole.

Roosevent, Moody, and Stimson were resolute in prosecuting antitrust violations. How resolute the current Justice Department is remains to be seen.

Both cases also required industry. Stimson and his staff invested countless hours developing and presenting their case. The current Justice Department has already done so as the Justice Department rarely proceeds with cases it does not have a good chance of prevailing on the merits.

Both Attorneys General believed the cases were brought in proper order. For Moody, he pushed for antitrust prosecutions. The current Justice Department conducted a thorough investigation, then proceeded once they believed they had a case.

More interesting, however, is where the cases may diverge. Were this done in moderation? The answer seems to be yes but for different reasons. Stimson brought just one charge, as a test case. The case against Apple is a civil case. Prison will not be an option. The Justice Department could have done more, in both instances. In terms for frugality, both cases cost significant sums but the Apple case will cost much more. It will involve significant litigation in advance of any trial. Most likely it will end with a settlement. Stimson’s case was relatively straightforward and smaller. Not only was it a moderate case but it was frugal.

What about tranquility and silence? Neither case was designed to achieve those virtues. Both sought to disrupt the status quo. Both generated significant public attention. That was the point. Both were symbolic.

This leaves justice, perhaps the most important of the virtues. From the government’s perspective, both American Sugar and Apple deserved these outcomes. Both companies caused injury to the public who had to pay more for the goods and services provided. It is unlikely, however, that American Sugar or Apple considered the cases warranted.

Ultimately, the case had little effect on American Sugar. It continued trading under the well-known Domino sugar brand. Yet the case made a significant difference to antitrust enforcement. It served as a model for future antitrust prosecutions and, more generally, white collar crime prosecutions.

Over the last several weeks, we have seen what virtuous prosecutions look like. What happens when something is not done virtuously? Next week will provide an example.

I hope you enjoyed this issue and that it made you stop and think. I would love to hear any comments, questions, concerns, or criticisms that you have. Leave a comment or send a message! Also, if you enjoyed this or if it challenged your thinking, please subscribe and share with others!