At the pleasure of the President?

Does the President's removal power give the President the authority to do whatever the President desires with the Justice Department?

In a classic scene from the television series, The West Wing, key members of the President’s staff, state, in turn, that they serve at the pleasure of the president. While none of them are members of the President’s cabinet, there is little distinction between a member of the president’s White House staff and a Cabinet official. Both are appointed and serve at the pleasure of the President. This means that if the President is dissatisfied with their performance, the Preident can remove them from office. What about federal prosecutors? Should there not be some independence from the White House in the exercise of federal prosecutorial discretion? This independence provides one of the few shields we have against partisan political prosecutions. Does that shield even exist?

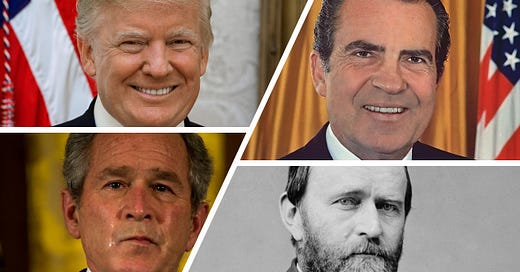

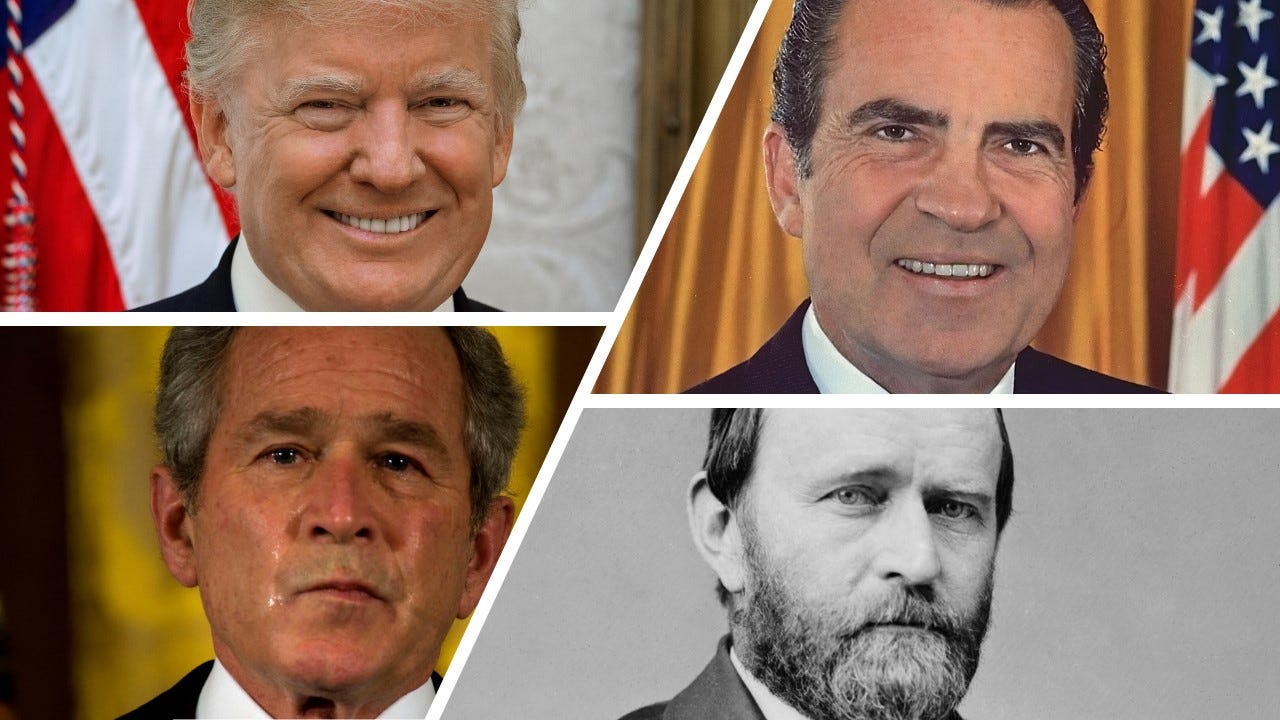

While President, during a conversation with a New York Times reporter, President Trump said that he had the absolute right to do whatever he wanted with the Justice Department. (Schmidt and Shear, 2017). The former President said this in the context of an investigation into former First Lady, Senator, and Secretary of State Hillary Clinton for maintaining unsecured national security information on her personal computer server. He continued by stating he would remain out of the matter in the hope that he would be treated fairly by the special Justice Department counsel, Robert Mueller, who was investigating the Trump campaign’s relationship to Russia during the 2016 election cycle. With this statement, former President Trump, at minimum, implied that presidents could order criminal prosecutions of particular people.

The relationship between the President and the Justice Department also served as a key aspect of former President Trump’s efforts to vindicate his claims that the 2020 Presidential election was stolen from him. In late December, President Trump sought a statement from the Justice Department that there was significant fraudulent activity in the November presidential election. Trump had initially sought the statement from Attorney General Bill Barr. Barr refused and resigned under pressure. Jeffrey A. Rosen, Barr’s deputy since 2019, became the Acting Attorney General. Like Barr, Rosen refused to provide President Trump with the statement he sought. Attention then shifted to others in the Justice Department who might be more suportive. Enter Pennsylvania House member Scott Perry. A staunch Trump supporter, Perry maintained contact with Jeffrey Clark, the Assistant Attorney General in charge of the Environment and Natural Resources Division of the Justice Department. Clark made it clear that he would endorse the President’s view point. Rumors began that President Trump would remove Rosen and the Deputy Attorney General, clearing a path for Clark to become the Acting Attorney General. Without explanation, however, the President never made this move and did not exert control over the Justice Department. (Risen, 2023)

This was hardly the first time that a sitting President attempted to exert more control over criminal prosecutions. In 2006, in a plan originating within the George W. Bush White House, the Justice Department removed numerous United States Attorneys. This was not the typical replacement that occurs with a change in President. Instead, the White House and Justice Department removed at least seven United States Attorneys whom they had appointed. Those removed were not “loyal Bushies” because they had not been sufficiently aggressive in prosecuting Democrats for public corruption or enforcing immigration laws. Several of the replacements had close ties to senior Bush White House officials. (Green and Zacharias, 2008).

Just a generation before, President Richard Nixon pushed to intervene in the prosecutions associated with the Watergate break-in and its subsequent cover-up. In Spring, 1973, Nixon moved Elliott Richardson from Secretary of Defense to Attorney General. Several months later, Nixon, frustrated with his inability to control the Watergate investigation of special counsel Archibald Cox, ordered Richardson to remove Cox. Richardson, during his Attorney General confirmation hearings, had promised the Senate that he would not interfere with Cox’s investigation. Consequently, Richardson resigned. Nixon then turned to Richardson’s deputy, William Ruckleshaus, to fire Cox. Having made the same promise to the Senate as Richardson, Ruckleshaus followed Richardson’s lead. This left Robert Bork, the Solicitor General. Rather than face the possibility of the Department’s top three people resigning within hours, Richardson tasked Bork with carrying out the President’s order. Ironically, Cox was replaced by Leon Jaworski, over whom Nixon had even less control. (Graff, 2023)

Lest one think efforts to control prosecution are a modern phenomenon, one of the firt major efforts to control federal prosecution occurred during President Ulysses S. Grant’s second term. In an administration beset by scandal, the St. Louis Whiskey Ring hit closest to home for the President. He lived on a farm just outside St. Louis and knew personally many of the people appointed to government jobs in St. Louis. This included the United States Attorney, William Patrick, and multiple revenue inspectors. When Treasury Secretary Benjamin Bristow uncovered fraud on an unprecedented scale amongst whiskey distillers and government revenue agents, Grant was outraged. When Patrick was slow to pursue prosecutions, Bristow and Attorney General Edwards Pierrepont arranged to have Patrick replaced by someone not connected with the tumultuous Republican politics of the time, David Patrick Dyer. Dyer was assisted by two special counsel, Grant-supporter Lucius Eaton, and Grant opponent, former US Senator John Henderson. During the investigation, evidence emerged that Grant’s trusted personal secretary, Orville Babcock, was, at minimum, aware of the frauds and likely helped cover them up. When prosecutors set their sights on Babcock, Grant took it as a personal attack. Grant ordered Henderson removed from the prosecution just weeks before Babcock’s trial. Grant also wanted Dyer removed but Bristow and Pierrepont threatened to resign if Grant did so. Deterred from removing Dyer, Grant provided a deposition on Babcock’s behalf, thus testifying against his own administration’s prosecution. This led to Babcock’s acquittal but the public outcry contributed to Grant not seeking an unprecedented third presidential term. (Ingram, 2018).

These four instances reveal there is a thin and delicate shield that protects federal prosecution from presidential interference. That shield, however, is not legal nor normative. Instead, it is a function of the president’s self-interest. In the Trump scenario, he most likely calculated that the Justice Department letter was not of supreme importance so he focused attention elsewhere. In the Bush scenario, he could have done more but focused his attention on the most narrow group to minimize the political fallout. Grant did likewise. Nixon, conversely, shows the shield’s delicacy. Most likely, had Bork not carried out the order, Nixon would have continued plowing through Justice Department officials until he found someone to do his bidding. His political reputation and capital could not get much lower. He had nothing to lose. Fortunately, someone of character stepped in to salvage the situation.

I hope you enjoyed this issue and that it made you stop and think. I would love to hear any comments, questions, concerns, or criticisms that you have. Leave a comment or send a message! Also, if you enjoyed this or if it challenged your thinking, please subscribe and share with others!

Sources

Michael S. Schmidt and Michael D. Shear, “President Says Inquiry Makes the US Look Bad” New York Times, Dec 29, 2017, pA1.

James Risen, “The Man With No Pants Is the State of Donald Trump’s Latest Indictment.” The Intercept, Aug 2, 2023.

Bruce A. Green and Fred C. Zacharias, “The U.S. Attorneys Scandal and the Allocation of Prosecutorial Power” 59 Ohio St. Law Journal 187 (2008).

Garrett M. Graff, Watergate: A New History Simon&Schuster (2023).

Scott Ingram, “Politics of Justice: Presidents Trump and Grant and the Problem of Investigating the Executive Branch” (November 1, 2018). Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3363358 or http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3363358