Introducing RICO

The Justice Department recently announced two major RICO cases. The first featured P Diddy and sex trafficking. The second featured the Peckerwoods and their white nationalist activities.

Justice Briefs is a weekly newsletter devoted to federal criminal prosecution. The federal government’s evolution over the last 230 years has given federal prosecutors significant discretion. Few realize it exists and even fewer know how it is used. Justice Briefs aims to make federal prosecutions and prosecutors more accessible to the general public. Please help me in this endeavor by subscribing and sharing with others.

Justice in Brief

In the Western District of Kentucky, four people were indicted for violating the Export Control Reform Act when they attempted to send more than 30 firearms to Iraq without a license. After purchasing the guns at gun shows, the defendants falsified various documents.

In the Western District of Tennessee, several former Memphis police officers were convicted of depriving a man of his constitutional right to be free from unreasonable force. The man dies from the injuries caused by the police officers.

In the District for the District of Columbia, two Chinese men were convicted in a scheme to defraud Apple to obtain authentic Apple iPhone components. The men sent counterfeit iPhones to Apple, hoping Apple would replace the counterfeit parts with real parts.

Racketeer Influenced Corrupt Organizations (aka RICO)

One of the most powerful federal criminal statutes available to federal prosecutors is the Racketeer Influence Corrupt Organization (RICO) charge. RICO broadens the traditional conspiracy offense, permitting the Justice Department to dismantle large conspiracies that operate more as an organization. Congress enacted the law in 1970 so that the Justice Department could more effectively dismantle large, organized crime families. By the late 1970s, the Justice Department learned that RICO was a powerful statue and implemented strict approval requirements. In any given year, the Justice Department prosecutes only a handful of RICO cases. When federal prosecutors announced two major cases in the last three weeks, it merits some additional attention.

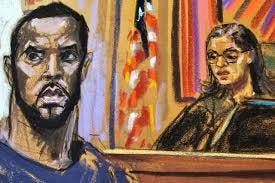

The Southern District of New York United States Attorney’s Office indicted music and business mogul Sean Combs for leading a racketeering conspiracy. According to the indictment, Combs “abused, threatened, and coerced women and others around him to fulfill his sexual desires, protect his reputation, and conceal his conduct.” To do this, Combs used his employees, resources, and organization. Combs and others in the organization “engaged in, and attempted to engage in, among other crimes, sex trafficking, forced labor, kidnapping, arson, bribery, and obstruction of justice.” While operating under different business names, Combs abused women emotionally, physically, verbally, and sexually. Those working with Combs knew that he engaged in this conduct. They intentionally aided Combs conduct his commercial sexual activity.

It began by luring women to the organization using its economic power and its role as a “gatekeeper” to the music industry. Once connected to the organization, the women were forced to engage in “elaborate and produced” sexual performances. Combs observed these for his own sexual gratification. While these occurred, Combs also distributed controlled substances to the participants, often without their knowledge of what they were ingesting. Combs and his associates maintained their control over the victims by promising to promote their careers, threatening to damage their reputation, and engaging in physical violence. As part of these objectives, Combs and his associates engaged in offenses including kidnapping, arson, forced labor, and sex trafficking.

Two weeks after the Combs indictment, the Central District of California United States Attorney announced an indictment against 68 members of the San Fernando Valley Peckerwoods gang. During the course of the racketeering conspiracy, the group profited from drug distribution and various forms of fraud. Members of the group identify themselve through tattoos and other items. These include the Confederate flag, the Nazi swastika, and the letters SFV. They communicate over various platforms to plan their criminal activities. The SFV Peckerwoods goals include financial profit from drug and fraud activities, control over SFV territory, and attacking members from rival gangs. To further these activities, the indictment referenced 140 overt acts, most of which involved online communications. Some communications espoused their white nationalist ideology. Others identified themselves as members and still others involved coded messages referencing drug transactions.

These two indictments reveal the breadth of RICO’s reach. The Combs RICO indictment involves sex trafficking and lurid videos. The SFV Peckerwoods indictment involves drug dealing and financial fraud. While both included large numbers of people, the Combs indictment was limited to Combs. The SFV Peckerwoods indictment included 68 people. Both covered conduct that spanned the course of more than a decade. It included innocuous conduct, such as electronic communication, and violent conduct such as robbery and assault.

RICO has such a broad reach because it prohibits anyone from (1) receiving income from, (2) exercising control over, (3) participate in, or (4) conspire with an enterprise engaged in racketeering activity. The statute further defines racketeering activity. The definition covers a wide array of criminal conduct under both state and federal criminal law. Covered state laws include “murder, kidnapping, gambling, arson, robbery, bribery, extortion, dealing in obscene matter, or dealing in a controlled substance.” The included federal criminal offenses cover even more conduct, ranging from extortionate credit transactions and straw purchases to economic espionage and from stolen property and copyright infringement to biological and chemical weapons. The key limitations are that there must be two of these offenses committed within a 10-year period and they must demonstrate at least a threat of continued criminal activity. The statute also defines an enterprise broadly such that it includes any association of people, regardless of whether it is a legally recognized entity.

Congress granted federal prosecutors such broad powers so that the federal government could more effectively prosecute racketeering. Concerns about racketeering emerged early in the 20th century, particularly in New York and Chicago. Groups working under various names sought to make profits from illegal conduct such as gambling, liquor, and prostitution. They protected these “rackets” by using violence and bribes. Rival organization members were assaulted or killed. Local law enforcement was bribed to look the other way. As these organizations gained money, they gained power, working to influence legitimate organizations, especially labor unions. By this time, federal prosecutors figured out how to prosecute the middle or low-level members but could not get the leaders. To reach the organization’s highest levels, Congress created RICO, criminalizing the mere association with such an organization.

When drafting the legislation, however, Congress could not target a particular group. Instead, it had to focus on conduct. After much debate, Congress settled on the two-offense requirement and listed a range of offenses often associated with racketeering. Over time the list grew. As the list grew, more organizations fit within the statute’s reach. With this expanded reach came the potential for abuse.

To protect its powerful tool from abuse, the Justice Department imposed approval requirements. Any prosecution under RICO must be approved by the Department’s Violent and Organized Crime Section. The United States Attorney’s Offices must submit a proposed indictment several weeks in advance. The Violent and Organized Crime Section attorneys review it to determine that the indictment is legally sufficient and meets Departmental criteria. By doing this, the Justice Department hopes to avoid prosecuting cases that are “unworthy” of RICO charges.

For the past 54 years, the Department has succeeded in preserving this important power. The Combs and SFV Peckerwoods cases demonstrate how broadly the RICO statutes extend. When the Justice Department brings these cases, they are newsworthy events. Observing how the Justice Department uses this power is a good way to determine if the Justice Department is living up to its name.

I hope you enjoyed this issue and that it made you stop and think. I would love to hear any comments, questions, concerns, or criticisms that you have. Leave a comment or send a message! Also, if you enjoyed this or if it challenged your thinking, please subscribe and share with others!