The First Special Counsels

The early history of federal criminal prosecution did not consider conflicts of interest. Instead, special counsels assisted with the most difficult cases.

Justice Briefs is a weekly newsletter devoted to federal criminal prosecution. The federal government’s evolution over the last 230 years has given federal prosecutors significant discretion. Few realize it exists and even fewer know how it is used. Justice Briefs aims to make federal prosecutions and prosecutors more accessible to the general public. Please help me in this endeavor by subscribing and sharing with others.

Justice in Brief

*In the Northern District of Illinois, a man entered a guilty plea to falsely representing the odometer readings in hundreds of used cars he sold. He purchased the vehicles from auto auctions, rolled back the readings, and then sold them to car dealers.

*In the Western District of North Carolina, two attorneys and an insurance broker were found guilty of tax fraud. They solicited clients for a “tax shelter,” when, in reality, they were taking the clients’ money.

*In the Southern District of Florida, the former Comptroller General of Ecuador was found guilty of accepting $10 million in bribes from a Brazilian company while serving as Comptroller General. Friends and associates, often unknowingly, created Florida accounts and businesses which were then used to launder the bribe money.

The First Special Counsels

Today special counsels handle only cases where the Justice Department has some conflict of interest. Usually the conflict occurs because someone close to the President or within the upper-levels of the Administration has committed some criminal act. This was not the original function of special counsels, however. Early federal prosecutors did not consider whether a particular prosecution presented a conflict of interest. Instead, special counsel were used in particular matters that requires special assistance. One of the first occurred in 1799 when the government prosecuted those associated with Fries Rebellion. They sought someone who was familiar with the German-Americans involved in the rebellion. Several years later, in the first political conflict of interest case— the prosecution of former Vice President Aaron Burr— special counsel were used along side the United States Attorney because of the legal complications presented by the case and the high stakes involved.

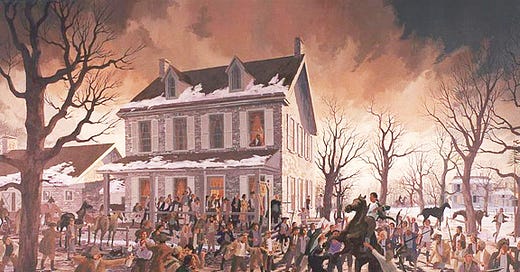

One of the first special counsels appointed was Samuel Sitgreaves during the prosecution of those involved in Fries Rebellion. The Rebellion occurred in 1798 as Germans in southeastern Pennsylvania opposed a direct tax on real estate. Pennsylvania assessed its share of the tax based on the value of the structure on a property. Value was determined by counting the windows and their size. This meant assessors had to go to each house and count windows. The counting process generated suspicion and resentment among the Germans living in the are north and west of Philadelphia. They refused to pay.

Refusing to pay the tax proved to be a poor strategy. The federal courts quickly issued summons for the delinquent tax payers. This meant the US Marshal and his deputies had to serve the tax payers. In some cases, it meant arresting them to ensure their presence in court. The residents plotted resistance. When one marshal stopped at a local tavern for the night with his prisoners, a group formed to force the marshal to release those in his custody. John Fries, for whom the rebellion was named, led an armed group to the tavern. After threats and negotiations, the marshal released the prisoners and reported back to Philadelphia. This ultimately led to treason charges against John Fries.

This was not new territory for Pennsylvania’s United States Attorney, William Rawle. Much like he had for the Whiskey Insurrection four years prior, Rawle traveled to the region and assisted with the collection of depositions. Also similar to 1794, not only did Rawle have a large collection of tax resisters, he also had to prosecute violations of the Sedition laws. This made for a busy court term. To make things more challenging, those indicted spoke better German than English. All of this led Rawle to seek assistance with these cases. He turned to a former Congressman from the region, Samuel Sitgreaves.

Sitgreaves was a devoted Federalist and had supported not only the tax but the Sedition Act in Congress. His support earned him an appointment to London as U.S. consul for claims under the Jay Treaty. Sitgreaves had two important qualifications in addition to his living in the region. First, while in Congress, he had studied the law of treason. This knowledge would complement Rawle’s experience. Second, Sitgreaves spoke German. He understood what was said and he understood the cultural dynamics at play.

When the case came to trial, Sitgreaves performed a key role. He presented both opening and closing remarks to the jury. His opening statement, in particular, set the stage for the government’s theory: any armed resistance to the enforcement of law constituted treason. It was the same argument Rawle advanced—successfully— during the Whiskey Insurrection trials. Yet, in this case, Sitgreaves expanded on it. Levying war included the intent to use force against the government. As Fries and the others involved did not use force, the government had to interpret treason more broadly than before.

The theory succeeded not once but twice. After the first conviction was reversed due to a biased juror, the government secured a second conviction. Fries was sentenced to death. However, after much debate, President Adams decided to pardon Fries.

The Fries prosecution represents the use of special counsel as an assistant rather than as a replacement. The case presented no conflict of interest yet the circumstances necessitated a special assistant. Several years later, another case arose that did present a conflict. Special assistants were hired. Yet, like in Fries, the special assistant was an assistant, rather than a replacement.

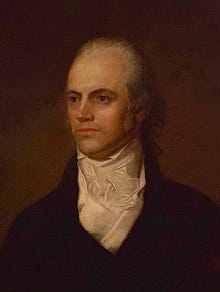

After serving one term as Thomas Jefferson’s vice president, Burr found himself replaced. With no political future in the United States following his killing of Alexander Hamilton, Burr set off on his own military expedition. Though the precise aim of the expedition remains unclear, Burr gathered forces on a island in the Ohio River between Ohio and Virginia. As preparations increased, people talked, and rumors circulated. They soon reached Kentucky’s United States Attorney who forwarded the information to President Jefferson.

As rumors spread, various officials began investigating. The investigations resulted in Burr’s indictment for treason in the District of Virginia. The indictments began a prolonged and complicated legal battle. George Hay was the United States Attorney for Virginia. He had risen to prominence several years prior when he defendant James Callendar, a Jeffersonian newspaper publisher, on sedition charges. Though Hay was a quality attorney, he would need assistance as this was the most controversial criminal prosecution in United States history. It had to be done right. The government sought assistance from John Wickham, the pre-eminent attorney of an outstanding Virginia bar. Wickham, however, had already accepted a spot on Burr’s defense team. Instead, the government turned to an outstanding young Maryland attorney named William Wirt, who would eventually become the longest serving Attorney General in United States history.

Wirt, Hay, and a third attorney, Alexander McRae worked well together, They also remained in constant contact with Jefferson’s Attorney General Ceasar Rodney. The case went to trial but the case was eventually dismissed when Chief Justice John Marshall ruled that the government failed to present sufficient evidence that Burr had engaged in levying war against the United States, despite the Fries precedent.

By today’s standards, however, neither Hay nor Rodney would have been anywhere near the case. It presented a textbook example of a conflict of interest. Jefferson, who also exchanged information with both Rodney and Hay about the case, hated Burr, whose supporters had helped undermine an important prosecution one year earlier. Burr had also made the election of 1800 the first to be decided by the House of Representative when he refused to yield to Jefferson’s election victory. If anyone had motive to target someone for criminal prosecution, it was Jefferson. The fact that both Hay and Rodney participated, and no one sought their recusal, reveals that conflicts of interest were not the reason for special counsel.

Obviously, much has changed in American criminal justice since these cases. We operate under different standards today. Yet, as evidenced by this series, special counsels do not minimize the politics. Using them makes no difference in the outcome. This applies equally to the first cases. At least when it comes to political influence, special counsels are not so special.

I hope you enjoyed this issue and that it made you stop and think. I would love to hear any comments, questions, concerns, or criticisms that you have. Leave a comment or send a message! Also, if you enjoyed this or if it challenged your thinking, please subscribe and share with others!