Who put the 'justice' into the Justice Department?

Though not the Justice Department until 1871, justice was first associated with federal criminal prosecution in 1806.

One of the more susprising things I learned while researching my book, Constitutional Inquisitors, was that early federal prosecutors did not talk about justice when determining which cases to pursue. Nor did they talk about justice following a verdict, whether guilty or not guilty. This surprised me because “doing justice” is the central tenet of prosecutors and those who study them. It is the fundamental concept. If the concept is so fundamental, it is reasonable to think that justice would appear in the vocabulary of the original federal prosecutors. But, it did not.

The first time justice appeared in conversations involving a federal criminal prosecution was 1806. It arose in the aftermath of a high profile criminal prosecution. The case involved former President John Adams’s son-in-law, who was accused of aiding Francisco Miranda embark on an expedition to liberate Venezuela from Spanish rule. At the time, the United States had a complicated relationship with Spain. Though not at war, the two nations were not on friendly terms. Miranda, a charismatic military figure, assembled a crew, including Adams’s grandson, for an expedition from New York to Venezuela. William Smith, who had married Adams’s daughter, Abigail, was the Port of New York’s Surveyor, which meant he granted Miranda’s expedition to Venezuela permission to depart. The government later alleged that Smith did this, knowing Miranda planned to invade Venezuela.

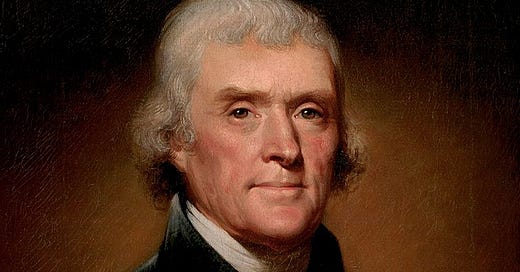

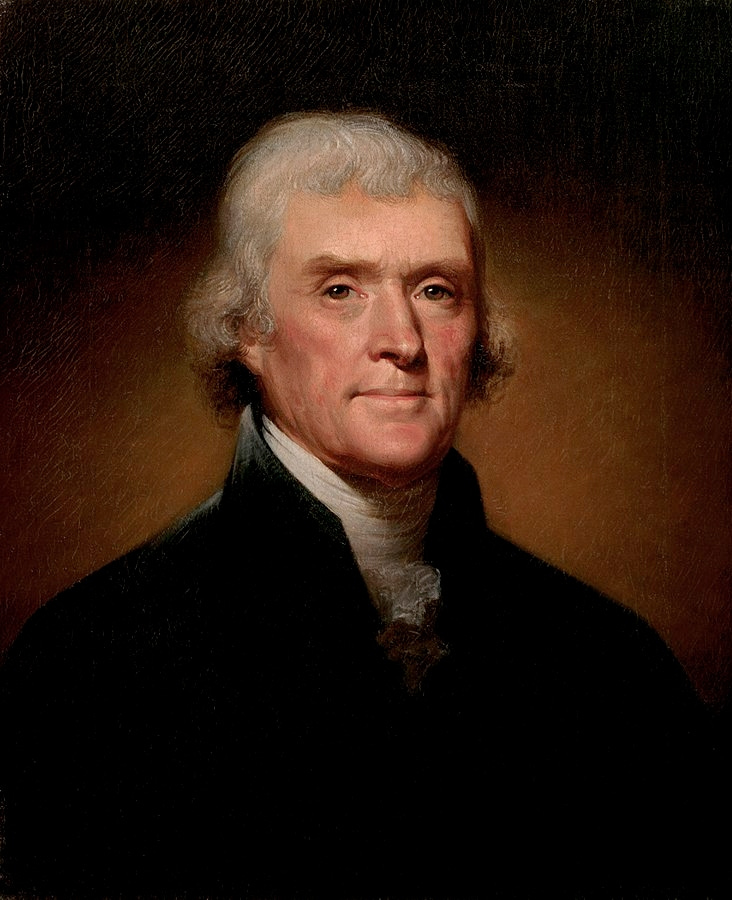

It did not take long for the Spanish government to learn what happened. Its representatives in New York knew Miranda and observed his departure. The Spanish government protested to United States Secretary of State James Madison. Madison consulted with President Thomas Jefferson. The two decided the United States must investigate the matter and prosecute the offenders. The investigation led to Smith and Samuel Ogden, a New York ship owner. Jefferson personally ordered the cases prosecuted.

The case quickly devlolved into a political squabble. New York Federalists quickly lined up to defend the pair. Their number eventually included Richard Harison, who had served as United States Attorney for New York and whom Jefferson fired upon winning the presidency. The prosecution also faced opposition from within the Republican ranks. Jefferson’s election was secured, in part, through Aaron Burr’s support in the northern states. Also a Republican, Burr served as Jefferson’s running mate. Once victorious, the pair quickly divided with Burr not returning as vice President for Jefferson’s second term. With the trial in Burr’s New York base, those still loyal to him saw an opporunity to undermine the now-hated Jefferson. One Burr loyalist, the United States Marshal, went so far as to ensure a jury favorable to the defense. The political manuverings eventually doomed the prosecution.

Following the inevitable acquittal, Jefferson summarized his thoughts in a letter to his Treasury Secretary, Albert Gallatin.

the skill & spirit with which mr Sandford and mr Edwards conducted the prosecution gives perfect satisfaction. nor am I dissatisfied with the result; I had no wish to see Smith imprisoned: he has been a man of integrity & honor, led astray by distress. Ogden was too small an insect to excite any feelings. palpable cause for removal of the Marshal has been furnished, for which good tho’ less evident cause existed before, and we have shewn our tenderness towards judicial proceedings in delaying his removal till these were ended. we have done our duty, & I have no fear the world will do us justice. all is well therefore.

In this passage, Jefferson reveals his sense of justice. The government’s attorney’s performed professionally and admirably. The defendants, essentially, got what they deserved. Jefferson recognized Smith’s personal situation and noted that Ogden was a minor figure. He implicitly recognized the bigger problems escaped. Jefferson then reflected on the Marshal’s removal. Apparently, the Marshal’s conduct did not suprise Jefferson and the President was merely waiting for sufficient evidence to make the change. In doing so, Jefferson demonstrated his awareness of the public’s reaction, factoring it into his decision-making. Finally, he honored the separation between executive and judicial. While he could have removed the Marshal immediately, Jefferson did not wish to interfere in the judiciary’s conduct of the case. These things, according to Jefferson, were the government’s duty in the case. Doing these things would lead to justice.

To Jefferson, justice was a sense or a feeling, rather than something tangible or observable. People were born with a sense of justice. In large measure, the sense of justice came from treating people equitably. What made something equitable, however, was not necessarily clear. Much depended on the situation. Jefferson also believed that different people could act differently and still act in accord with justice. People perceived justice differently. This did not bother Jefferson because, he believed, true justice would be administered eventually, whether through nature or some super-natural figure.

This is why Jefferson found satisfaction in the verdict even if it was not the result he desired. Justice was done because the government did its duty and the people decided for themselves whether the conduct merited punishment.

Today, we leave it to the government to administer justice. The government’s duty is to determine the case’s worthiness for prosecution. Worthiness is seen as good evidence implicating the defendant in a sufficiently serious offense. We do not trust juries to decide whether punishment is appropriate for the situation. We do not give them the chance as more than 90% of federal criminal cases result in a guilty plea. Although Jefferson incorporated justice into the forum of federal criminal prosecution, his conception of justice differs significantly from what we practice today.

I hope you enjoyed this issue and that it made you stop and think. I would love to hear any comments, questions, concerns, or criticisms that you have. Leave a comment or send a message! Also, if you enjoyed this or if it challenged your thinking, please subscribe and share with others!

Sources

“From Thomas Jefferson to Albert Gallatin, 15 August 1806,” Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Jefferson/99-01-02-4170.

Matthew Crow, "Thomas Jefferson and the Uses of Equity", 33 Law and History Review 151 (2015).

Scott Ingram, Constitutional Inquisitors: The Origin and Practice of Early Federal Prosecutors, Johns Hopkins University Press (2023) 168-175.